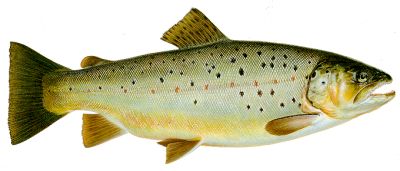

The River Brown Trout

|

A chalkstream brown trout.

The heavy build, red spotting and red margin on the adipose

fin are sure signs of good feeding in the most productive of

trout streams. |

Although scientists recognise no genetic distinction between the brown trout, or 'brownie', and most other varieties of Salmo trutta, the Old World trout, many anglers and naturalists prefer to call it Salmo trutta fario, and distinguish not only between lake and river varieties, but between the trout of the lowland chalkstreams and the smaller fish of spate rivers. Although their lifestyle and behaviour are similar throughout most of their range, brown trout can vary considerably in size and coloration according to the waters they inhabit and the available food.

Most river brown trout spawn during early winter (November and December), migrating upstream to the shallow gravel runs of the main river or the tiny feeder streams. They then drop back downstream. Through the spring, summer and early autumn river brown trout remain very solitary fish, with each individual keeping to its lie and chasing off any lesser trout and parr that might intrude. From quite a small area, possibly only three yards long and one yard wide, they obtain all the food they require.

Much of their food is carried to them by the current: nymphs and larvae of aquatic insects that have been washed from the river bed, mature nymphs and pupae that rise from the riverbed to hatch at the water surface, and flies that have just hatched or been blown from the surrounding countryside on to the water surface. When the flow carries little potential food, river brown trout will grub around in the weed and gravel of their lies for freshwater shrimps, water hog-lice and immature nymphs and larvae.

The chalkstreams of England and northern Europe are far more productive than the spate rivers, and are considered by many to be the greatest of all trout rivers for the quality of their water. They are fed from massive underground reservoirs in the chalk downlands, so the flow is constant, save in the driest of summers; and except after the most torrential downpours the rivers rarely rise more than a few inches above their usual height. The riverbeds are very stable and support prolific growths of water weed, which in turn support a huge population of invertebrates on which the trout can feed.

In such waters the trout grow quickly, and in the past, could attain great size. In 1832, Stephen Oliver recorded a brownie from Yorkshire's Driffield Beck that was 31 inches in length and weighed 17 lbs. (Scenes and Recollections of FIy-Fishing). The Linnaean Society of London reported a brown trout caught from the Wiltshire Avon at Salisbury in 1822 that scaled 25 lbs. The latter was kept alive: 'Mrs Powell, at the bottom of whose garden the fish was discovered, placed it in a pond, where it was fed and lived for four months.' Today the combined effects of heavy fishing pressure and artificial stocking make it highly unlikely that fish of these sizes will ever be caught again in chalkstreams. Today a 4 lb. trout is considered a large fish.

Most of the other rivers and streams inhabited by the wild brown trout are rough, boulder-strewn torrents that drain regions dominated by high moor and mountain. After heavy rain, the huge volume of water draining through the steep slopes of the uplands will cause the river to rise rapidly. During periods of drought, these rivers shrink to mere trickles, exposing large banks of bare gravel. In the heat of the summer sun, or in winter weather, these banks may almost be sterilized of animal life.

During a powerful spate large numbers of the river invertebrates will be crushed by boulders rolling down the bed of the river; in winter spates a high proportion of trout redds will be smothered by shifting sand and gravel. Adult trout are not immune in severe spates: following one terrific flood more than a sackful of dead wild trout were collected from a short length of the tiny West Allen Burn in Northumberland.

|

Northumberland's (England) West Allen River is a typical upland spate stream. In prolonged droughts it shrinks to a mere trickle; following heavy rain it is a raging torrent. |

Brown trout can often cope with such extremes of water flow. In droughts, when the river is low, they may become nocturnal in habit. They will seek the cool still pools beneath the shade of overhanging trees, or the aerated pools beneath waterfalls. Then, come sunset, they will move into the shallows to feed. When the river is in spate the trout will seek the quieter corners, often amongst flooded bankside vegetation, where the flow is less.

Spate streams produce relatively little food, so the trout grow slowly. In some of the moorland streams of northern England and Scotland, mature four-year-old trout may scale as little as l lb. less than a fifth of their chalkstream relatives.

Spate river brown trout can vary considerably in appearance, and experienced naturalists and anglers have long distinguished between the wild trout of particular rivers. In the third edition of his A History of British Fishes (1859) William Yarrell quotes the great Victorian angler Lord Home: 'There are two considerable streams in this country which take their rise at no great distance from each other, the Whitadder and the Blackadder, the latter tributary to the former. The Trout of Whitadder (White water) are a beautiful silvery fish, but good for nothing; those of the other dark, almost black, with bright orange fins, and their flesh excellent.'